International demand for great apes in the zoo and pet industries is fueling trafficking, but change could be on the horizon if CITES seizes the moment.

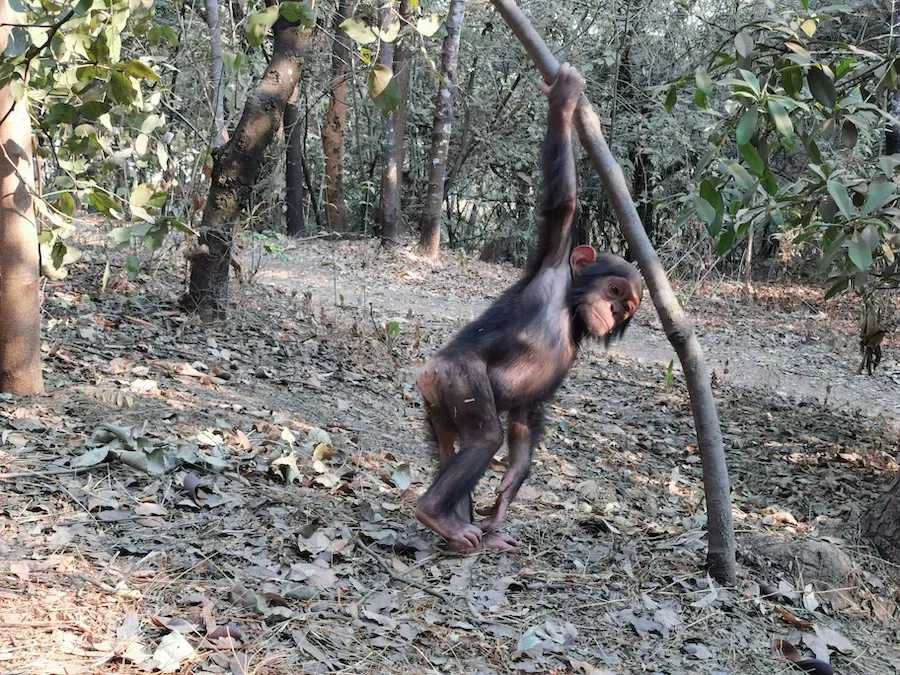

At less than one-year-old, Sana’s future is already partly decided. The tiny female chimpanzee is a trafficking survivor who has irreversible injuries. Due to these impairments, she can’t have babies on her own in the wild, as she will need to deliver by C-section. As studies also show, early trauma can scar chimpanzeesthroughout their lives. So Sana may grapple with social and emotional issues due to losing her family as an infant.

In other words, Sana has been robbed of a great many things in her short time on Earth. At the sanctuary where she now resides — J.A.C.K Primate Sanctuary (Jeunes Animaux Confisqués au Katanga) in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) — other young non-human primates have endured similar losses. They also have peers in sanctuaries elsewhere in Africa, with rates of great ape poaching, infant capture, and trafficking attempts, variously growing in several range states since 2020, according to investigative findings published earlier this year.

Chimpanzees, orangutans, gorillas, and bonobos, are all endangered or critically endangered. So the Earth’s dominant great ape — aka humans — needs to respond forcefully to the trafficking problem and other threats going forward.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is holding a Standing Committee meeting between 6 and 10 November. At the event, Liberia is calling on the committee to back new proposals aimed at addressing the trafficking issue, offering some hope that action could be on the horizon.

A Disaster

Sana arrived at J.A.C.K, along with Marie, a rescued blue monkey, in early September. They came to the sanctuary just a week before a dismal anniversary. On 9 September 2022, kidnappers snatched three young chimps — César, Monga and Hussein — from J.A.C.K in the middle of the night. The youngsters were never to be seen again.

Ransom videos sent by the kidnappers provided the last haunting images their human caretakers have of the chimps. But Franck Chantereau, who runs the sanctuary with his wife Roxane, is determined not to let their memory fade. He circulated a petition in the lead up the anniversary, urging people to sign it in an attempt “to keep their memory alive.”

J.A.C.K opened in 2006 and relies on its dedicated teams of keepers and other staff to provide a refuge for confiscated primates.

In DRC and other states where they live, primates are targeted both for their meatand for trafficking, mainly of youngsters, into the international zoo and pet trades. The problem has intensified in the last couple of years, according to Chantereau.

“It is just a disaster and it seems that the world is not taking paying enough attention to the problem,“ he says. “I don’t know what is going to be left honestly in the next five to 10 years.”

In the case of trafficking, it’s estimated that between five to 10 individual apes die for every stolen infant because people may “shoot the whole family in order to get the babies,” says Chantereau.

The Pan African Sanctuary Alliance’s (PASA) head of campaigns and policy, Iris Ho, paints a similar dire picture. PASA is a coalition of sanctuaries, wildlife centres, and other partners, that works to protect Africa’s primates. It has 23 members located in 13 African countries.

Ho says that she was aware of 27 young chimp and bonobo rescues in the DRC alone this year by mid-September, while wildlife trade investigator Daniel Stiles warns that trafficking of infant gorillas picked up in recent months. The situation is certainly at crisis levels in central Africa, according to Ho, with the same being true to some extent in west Africa.

Stiles authored a report titled “Empty Forests: How politics, economics and corruption fuel live great ape trafficking” in April. Produced by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), it pointed to a surge in international demand for live African apes in recent decades.

Moreover, the organisations and entities meant to control illegal trade in great apes “are failing to do so,” according to the report.

Legal Trade in Apes

CITES has an integral role to play in addressing the issue of trafficking. It is the treaty body that regulates the international trade in many wild species, including great apes.

The body has three different appendices for species, depending on their known risk of extinction. Trade restrictions and permitting requirements for each appendix vary accordingly.

CITES lists all great apes in Appendix I, which offers the highest level of protection. Broadly speaking, commercial trade in Appendix I species, meaning trade that primarily aims to obtain financial benefit, is not supposed to occur. However, exemptions exist, including that if Appendix I species are bred in captivity, then commercial trade is possible.

To conduct such commercial trade, however, breeding facilities should be approved by their country’s CITES authorities and added to a CITES register.

There are no CITES-registered facilities for breeding great apes, the GI-TOC report highlighted. This means that no commercial trade of great apes, including captive-bred individuals, should happen.

When the necessary criteria is met, non-commercial trade can be permitted for other defined purposes, such as zoos, circuses, and reintroduction to the wild.

CITES Wildlife TradeView records show that countries reported importing 188 live great apes as “direct” trade between 2016 and 2021. Direct trade refers to animals imported straight from their country of origin. Most of the apes were alleged to be bred or born in captivity and the transactions included some individuals listed as traded for commercial purposes.

Legal Pathways for Illegal Trade

The existence of a legal trade in endangered species can provide avenues for illegal trade to happen. This appears to be the case with great apes, according to the GI-TOC report findings.

The report said that captive wildlife facilities involving great apes may operate as both breeding outfits and private zoos, with the latter seeing a massive proliferation in recent years. It further asserted that certain “captive wildlife facilities are increasingly acting as centres for laundering wild-caught animals and illicit trade.”

In comments to National Geographic, Stiles explained, “Registered zoos provide legal cover in the guise of rescue or conservation centers. They also offer laundering facilities for animals smuggled in and sold as captive bred.”

Co-founder of Liberia Chimpanzee Rescue and Protection (LCRP), Jenny Desmond, shares these concerns. LCRP is a rescue centre in Liberia, founded by Desmond and her husband Jimmy, to protect wild and orphaned chimpanzees in the country.

Desmond says, “knowing that sophisticated criminals find creative ways to ensure their supply, the front of ‘sanctuary’ has become a way for traffickers to secure, source, and trade apes without any obstacles.”

Some traders also openly advertise apes on social media platforms, according to the GI-TOC report. It explained, “A video post of a chimpanzee infant dressed in children’s clothing, for example, can quickly reach numerous potential buyers. The trade deals are then negotiated out of public view, in private-messaging apps.”

Abuse of CITES Rules

CITES characterises captive breeding of species as beneficial to wildlife, on the basis that it can lead to less exploitation of wild individuals. However, it can also be detrimental, with abuse of CITES’ relevant provisions facilitating trade in threatened species that would otherwise be forbidden.

Abuse of CITES’ captive-bred trade provisions is widespread, according to Monitor Conservation Research Society’s Chris Shepherd. It’s almost always cheaper and easier to capture wild animals than raise individuals in captivity, he says, and there is little meaningful scrutiny of captive breeding claims on the import and export sides of the trading chain.

This means that too often “the parent stock was harvested illegally or the animal that is being imported as captive bred has never been in a captive breeding facility and was directly taken from the wild,” Shepherd argues.

Rooting out illegitimate activity within breeding operations is essential because captivity-based sources make up a significant part of CITES-regulated trade in wild species.

Exporting countries reported more than 120 million direct animal trades by number — referred to as “specimens” — between 2016 and 2021. Over 68% of these specimens, excluding ranched animal trades, were allegedly born or bred in captivity, according to the body’s records. These figures include trade in various specimens, such as blood and tissue, skins, eggs, and other body parts or products derived from animals.

For direct trade in solely live individuals reported by number, captive births and breeding accounted for around 55% of the over 36 million animal trades that exporters reported during the period.

Countries also report trade in animals using other measures, such as kilograms, litres, and metres, so the above figures do not represent the entirety of trade in animals during the period.

Commercial Zoos

Zoos were the destination for most traded live great apes in the CITES records. This industry enjoys its own purpose of trade category, separate to the commercial classification.

However, a 2022 brief by the South African nonprofit EMS Foundation argued that many zoos could be considered commercial entities. Citing evidence from wildlife trade investigator and filmmaker Karl Ammann, it asserted that “commercial trade in critically endangered animals continues by simply entering purpose code Z (which applies to zoos), rather than purpose code T (which applies to commercial transactions).”

That zoos can be commercial entities is in no doubt. Indeed, the CITES Secretariat communicated by email that while some CITES parties use the Z code for all zoo imports, others use the T code in some instances. The Secretariat oversees the working of the Convention.

The EMS brief also highlighted examples whereby exporters variously utilised the Z code and the T code in sales of species to the same captive breeding facility, a disconnect that should raise alarm bells.

EMS suggested that determinations on whether captive wildlife facilities fall into the zoo or commercial category should partly depend on their financial activities and what they subject the animals to, such as using them in performances.

CITES is working on providing clarity for when different purpose codes apply. But to date it doesn’t appear to be adopting a ‘follow the money’ approach to defining the zoo code.

Great Apes Task Force

At a Standing Committee meeting in November, which is made up of country delegates representing various regions, CITES will take stock of its efforts to protect great apes.

It will review a report on great ape conservation and trade prepared by the Secretariat. The report contains recommendations that encourage parties to improve enforcement measures, collaboration, information gathering, and conservation.

Meanwhile, Liberia has submitted proposals to curb illegal trade in African apes for the committee to consider. It is asking the committee to recommend them for adoption at CITES’ next conference of the parties — CoP20 — which will take place in 2025. The committee decides matters by consensus or vote.

LCRP’s Desmond says Liberia has the world’s second largest population of western chimpanzees, along with the largest intact habitat for the species. She highlights that though national laws exist to protect them, “chimpanzees are under siege in Liberia with a loss of [an] estimated 10% of our population in the past 10 years solely through the rampant bushmeat and pet trades.”

Desmond adds, “Chimpanzee trafficking is local, regional and global. It is an immense and urgent situation. Regional and international collaboration, coordination, oversight, and shared intelligence are the only way we can combat this devastating crisis.”

Liberia’s proposals include calling for the creation of an African Great Apes Task Force. CITES has targeted task forces for other groups of species, such as big cats, and established one for apes in the past.

Having a dedicated task force for African apes would enable CITES to review and improve upon its existing commitments.

For instance, one of the CITES parties’ existing commitments is strengthening “anti-smuggling measures at international borders”. Despite this, the GI-TOC report asserted that apes are often trafficked across borders – mainly by air – with China, the UAE, and increasingly Libya, among the key ultimate destinations. The apes may be concealed in shipments of other species, using mislabelled documents, it said.

J.A.C.K’s Chantereau suggests the failure of countries to stop trafficked animals getting through borders could be addressed by involving experts in the identification process at customs. He also says that a wider rollout of electronic permits in CITES, which still largely uses a paper-based permitting system, would greatly help to reduce the use of fraudulent paperwork.

A task force could dedicate attention to these sorts of issues, along with the suspected abuse of CITES’ other relevant processes, and more.

PASA’s Ho cautiously hopes the discussions at the meeting will lead to some progress after great apes were largely left off the agenda at CITES’ last conference of the parties – CoP19 — in 2022. This omission, along with the Standing Committee failing to back prior suggestions aimed at ensuring apes receive focused attention, has left them somewhat “out of sight, out of mind,” Ho says.

Holistic Action

Liberia’s submission also outlines other commitments that the Standing Committee could recommend for adoption at the next CITES CoP.

These include building databases of known captive and wild apes, using artificial intelligence technology and DNA, for better detection of the origin of trafficked individuals. Databases exist to detect wildlife crime in other instances, such as the DNA database built to tackle rhino poaching.

In addition, Liberia proposes the development of strategies to ensure that ape sanctuaries meet high operational standards.

Naturally, meaningful oversight of captive care facilities would be necessary to enforce high standards, which Desmond suggests could help to thwart the laundering of great apes by illegitimate operators.

More broadly, she says high standards are critical for the welfare of individuals and to ensure that genuine sanctuaries meet the “larger responsibility” they have, namely safeguarding endangered species.

Rescue centers do this by helping individuals in their care to “recover, thrive, learn natural behaviors, live with others of their kind, retain their languages, cultures, and genetic diversity, and so much more.” In turn, what rescued apes teach their caretakers informs global conservation efforts and “feasible future reintroduction of great apes” to the wild will rely on these populations.

“Standards of welfare and care become even more important when we consider both the individual and the species,” says Desmond.

Echoing an earlier proposal from Gabon, Liberia also recommends that the task force develop “concrete strategies” with other multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs), such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, to tackle threats like habitat loss.

Illicit trade in great apes is linked to deforestation and habitat loss, along with people’s livelihoods, Ho highlights, so collaboration across MEAs is important. Deforestation makes it easier for traffickers to access great apes in their forest homes, while habitat loss can push wild apes closer to human communities. Add in insufficient livelihoods and high consumer demand and it’s a perfect storm for trafficking.

Relatedly, another of Liberia’s suggestions calls for establishing projects with relevant communities focused on sustainable livelihoods and habitat restoration.

In a further recommendation, Liberia calls for supporting range states in preventing and mitigating zoonotic diseases, via their One Health Program. As the COVID-19 pandemic made clear, the wildlife trade poses a considerable risk of diseases being transmitted from other animals to humans and vice-versa. This is a threat to people and wildlife, which the holistic ‘one health’ approach seeks to address.

Villains and Heroes

The GI-TOC report spotlights corruption as another major mountain to climb in tackling great ape trafficking. Corruption is an issue as old as (human) time and not one that is easily surmountable. But for as long as the world has had villains, it’s also had heroes. Thankfully, there is no shortage of the latter in the great ape trafficking situation either.

From communities and rangers that ensure apes are safe in their homes, through to rescuers and legitimate sanctuaries that liberate and nurture survivors, many champions exist. As Chantereau puts it, “You have heroes in Africa who are risking their lives trying to protect the last great apes.”

The surviving infant apes are also heroic, as are their families who perished trying to protect them.

Mpo’s story illustrates this well. When the young chimp was seized from traffickers, he was still clutching hair of a family member, presumably his mother. He ultimately let the hair go to take food from his rescuer, which Chantereau characterised as Mpo ‘choosing to survive.’

Summing up the courage to go on in the face of these young apes’ trauma is no small feat. Chantereau says when the sanctuary receives an orphan like Mpo, “you can look at him and, in his eyes, you can see he has lost everything. You can see he is empty.”

But very, very slowly, these young apes can gain in confidence and begin to trust their human caretakers. After all they’ve suffered at the hands of humans, through both exploitation and inaction, Chantereau says “they still have the grace to forgive us.”

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.